| | Korean

Lessons

by Leon of Leon's Planet, ©

2000-present

Updated 2022/05/09 (That's how Koreans write their dates)

Foreword: "Origin of Korean Script"

(Skip

this Foreword)

| The Korean script is called Hanguel.

The

word Hanguel is composed of two morphemes: Han (Korean) and

Geul

(script).

The Korea script was created

(or "invented" as it is commonly written) by a team of scholars

commissioned by King SeJong in 15th

century A.D.. All of the Koreans I've ever met (and I've met quite

a lot in ten years of living in Korea) believe that their script is

unique in that it was not modeled after any existing script. This

erroneous belief is perpetuated through Korean school textbooks, Korean teachers, and

Korean websites.

An example of Korean collective thought can be found on various

websites, one of which is wright-house.com,

and which reads:

| Unlike almost every other

alphabet in the world, the Korean alphabet did not evolve. It

was invented in 1443 (promulgated in 1446) by a team of

linguists and intellectuals commissioned by King Sejong the

Great. |

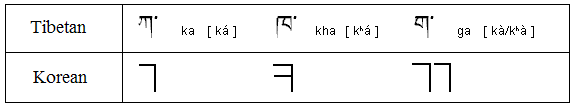

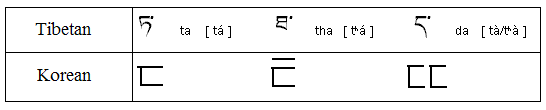

However, anyone who does

his/her research can clearly see that there are some remarkable

similarities between the Korean consonants and Tibetan consonants.

Omniglot.com,

in an article about the Korean writing system, has this written on its

website:

| King Sejong and his scholars

probably based some of the letter shapes of the Korean alphabet

on other scripts such as Mongolian

and 'Phags

Pa. |

| Personally,

I think it was based off of the Tibetan script. |

|

|

|

|

"Mongolia"

in

Mongolian script |

"Mongolia"

in

Phags Pa script |

"Mongolia"

in

Tibetan script |

"Mongolia"

in

Korean script |

With all due respect to

Omniglot.com, I disagree about the Mongolian script. I lived in

Inner Mongolia for 1 year and Outer Mongolia for 5 years. The

Mongolian script looks nothing like the Korean script. HOWEVER, I like the fact that somebody has used

logic by suggesting that the script was based partly (at least) on some

other script that existed at the time. There are some similarities

between the Phags Pa script and the Tibetan script (which is

unremarkable because the Phags Pa was invented by a Tibetan monk).

It was supposed to be a sort of written "lingua franca"

between all the languages of the Far East. It was kind of a hybrid

of the Mongolian script and the Tibetan script. However, I see

much more of a similarity between the Korean script and the Tibetan

script. (Read on and you'll see why).

Wikipedia.com

has an article about "Hangul" [Hangeul]. In that

article, the following is written:

| King Sejong was one of the

best phoneticians of his country, and his interest in phonetics

is confirmed by the fact that he sent his researchers 13 times

to a Chinese phonetician living in exile in Manchuria,

near the border between Korea and China. |

That, if true, would clearly

suggest that King SeJong (the founder of the Korean script) had research

done before (and during) the making/inventing of the new script.

Furthermore, would it not be logical to assume that King SeJong's

"team" of script-inventors were highly educated individuals,

who knew of and researched existing scripts of the times?

The article on Wikipedia

& the Wright-House

article show how the Korean script (Hangeul) was based upon the

articulations of the mouth. I do not wish to dispute that.

It is a very interesting idea. Incidentally, the Tibetan alphabet

is categorized almost exactly the same way. And it is possible

that the Tibetan script (and the script after which it was modeled,

namely Sanskrit) were invented in similar ways.

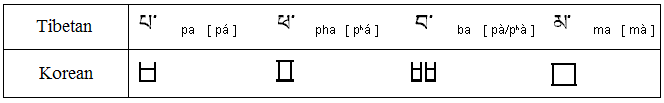

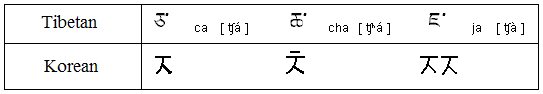

Other similarities between the

Tibetan script and the Korean one include:

- both

are written left to right (although

Hangeul can also be written top-down)

- both are written in syllabic clusters

- Tibetan syllables are separated by dots.

- I believe that the same was done in Hangeul anciently.

Now

you may judge for yourself

|

Tibetan

Script & Korean Script Compared |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

WARNING

WARNING

If you are an expatriate English

teacher in Korea, I would caution you NOT to try and enlighten your

students about the above information (as I have tried), because you will quickly become the

most unpopular teacher in the school, and your job will be in jeopardy (as

was mine). Whenever your students start to brag about the originality

of their script (Hangeul), just smile and say, "That's what you

think." And leave it at that. I tried to enlighten my

students once... notice the word "once". Believe me, it's

not a good idea, and you won't succeed in convincing them, no matter how

well you present your arguments. So, I'd advise not getting into it

with them. If you want, you may give your

students the URL for this page, and let them discover the truth on their

own. And, I'd appreciate the "hits" on my website.

|

| For more info on the Tibetan script,

click

here.

|

Now,

without further ado,

Let's

start to learn Korean!

FYI

|

Table of Contents

(FYI)

Preface:

How to learn Korean

Lesson 1: Romanization of Korean letters

Lesson 2:

Numbers

Lesson 3: Consonant Pronunciation

Lesson 4: How to read Korean

words

Lesson 5: Korean Honorifics

Lesson 6: The Korean Imperative

Lesson 7: The Korean Interrogative

Lesson 8: Requesting in Korean

Lesson 9: Korean Honorifics: Word Changes

Lesson 10: Korean Culture and

Language (TITLES)

Lesson 11: Restroom Talk (Where is the restroom?)

Lesson

12: Restaurant Talk

Lesson

13: Korean Grammar

|

Preface: How to

learn Korean

Preface: How to

learn Korean

(This is a "must

read" for any serious learner of the Korean language!)

Recently, I've received some inquiries about the best way to learn

Korean. So, I'd like to address that issue here, in the preface.

I always say that the best way to learn any language is "every

way". And what I mean by that is using a multitude of

methods. Here are some things to consider when learning any

foreign language, BUT MOST ESPECIALLY WHEN LEARNING KOREAN:

1. DECIDE ON A PURPOSE

It is perhaps best to decide what one's purpose is for learning the

language. For example, If one wishes to only read the language,

then it is not necessary to speak it or comprehend it when spoken.

Once you decide what your purpose for learning the language is, it

would be good to set goals.

2. EXPOSURE to the LANGUAGE

The next thing to consider, is exposure to the target language.

Obviously, the more exposure to authentic language, the better. Immersion

in the culture is by far the best way to learn a language because it is

learned in a meaningful context.

3. MY OPINION OF TEXTBOOKS

Text books do not always give "authentic" language, and

YET, they are not totally worthless. They are good for beginners,

and for increasing vocabulary knowledge. The big problem I have

with textbooks and learning the Korean language is they generally do not

teach honorifics, which is a HUGE part of the Korean language. For

more information about honorifics, please see my lesson #5.

I used textbooks mainly as ideas for topics to study and to increase

my vocabulary. I learned a lot through language exchanges with the

Korean people. A warm-blooded person is so much better than a

cold, dead textbook.

4. RELIABILITY OF REFERENCE MATERIALS

In the information age, we have come (most of us) to expect a certain

standard from certain sources of information. One thing I never

did when growing up was question the authority of a dictionary

(lexicon). I may have thought, well, this dictionary has more

lucid definitions than another one, but they are were correct. The

problem is with bilingual lexicons/dictionaries there are no

definitions, only TRANSLATIONS. And I hate to burst your bubble,

but some of those translations are WRONG! I have studied Korean

for 10 years and I have made a list of the errors commonly found in the

English-to-Korean & Korean-to-English bilingual dictionaries.

To see the list, click on the link below:

Click on link above to go to my "Dictionary

Errors" Page. You'll thank me.

5. KOREAN GRAMMAR Please be advised

that Korean collective English grammar is atrocious. The reason for

this is of course, faulty teaching and faulty reference materials.

The collective errors of the Korean English Education system have been

perpetuated for years. For example Mr. Seong Mun's English

Grammar Guide is considered a "BIBLE" of ENGLISH GRAMMAR in

Korea. And yet, it is replete with errors. This has repercussions

upon the would-be Korean-language Learner. Let me explain by

example. Koreans are taught that the way to say: "Naneun

((sth))

shireoyo," is: "I hate

((sth))."

[sth

= something].   WRONG

TRANSLATION!

WRONG

TRANSLATION!

It

gets confusing, because most Koreans do not really understand their own

grammar (and this by their own admission). Every Korean I've ever met (who addressed the topic) has

told me that their Korean grammar classes were harder than their English

classes. And, yet, I do not agree that the Korean grammar is all

that difficult. Yes! It is different from English grammar, but

fully apprehensible. In the example given above,

"Na" is a pronoun which refers to oneself. The particle

"neun" which is attached thereto is ambiguous to Koreans,

because they don't know how to classify it. By default, the word

"Naneun" usually gets translated as "I", and yet this

is usually incorrect. [Notice, I wrote "usually", because

there is ONE instance when it would be correct and that is when it is used

with the copula. Copula = be.] Dr. Ramstedt, a Finnish

linguist, classifies the "neun" (or sometimes "eun")

particle as the "emphatic particle". Therefore, the

correct translation of "Naneun" would be: "In my

case" or "Regarding myself". It is NOT the subject of

the sentence, except with the copula (be verb).  Correct

Translation Correct

Translation

Therefore,

the sentence: "Naneun ((sth)) shirheoyo," should be

translated as:

"In my case, ((sth)) is hated." The word "Shirheoyo"

is an intransitive verb (and it is passive voice). There is no object in the sentence. Some

people have argued with me on this, but what I'm about to say is 100%

true... Naneun is NEVER the subject of a sentence. It

never has been and never will be the subject of a sentence, because it

means: "In my case." So,

keep this in mind when learning Korean. 6. ROMANIZATION OF KOREAN

ALPHABET Any resources that were printed before the year

2000, will have a different Romanization than the one currently used in

Korea. This is another thing to be aware of. I admit that the

current Romanization, which is the one I use on this webpage, is better

than the previous one, it still presents some problems for Korean-language

Learners. This will become apparent in Lesson 1. 7.

RECOMMENDED ORDER OF STUDY I recommend that you start with

two things: (a) Start memorizing some useful phrases.

When I first went to Korea in 1995, I only knew three phrases: Eolmaimnigga?

(How much?), Gamsahamnida. (I'm grateful.), & Annyeonghashimnigga?

(Are you safe & peaceful?)--the common greeting in Korea.

[Note: Please note that most textbooks will translate Annyeonghashimnigga?

as "How are you?" That would be an incorrect

translation. There is a correct way to say, "How are you?"

but nobody uses that greeting in Korea.] (b) Start, also,

building your base vocabulary. The way I did this was

two-fold. Firstly, every night I would make a list of words that I

wanted to learn, and I would look them up in a bilingual dictionary.

Then, I would memorize them. Secondly, I carried a bilingual

dictionary with me every where I went and I would look up the words on the

signboard in my dictionary. My favorite bilingual dictionary

in Korea is Dong-A PRIME, because it has the most up-to-date and most

accurate translations (although it still is not perfect). You can

buy it online by clicking on the link(s) below: Dong-a's Prime English-Korean Dictionary Then,

once you have about 100 words memorized, I would start learning to make

sentences. Korean is a SOV language. That means that

the syntax is Subject-Object-Verb. One consistent thing about

the Korean language is that the verb is ALWAYS the last word of the

sentence. Quite often, the subject is dropped, when it is

implied. Other languages do this as well. They are called

"pro-drop" languages. But, Korean is unique in that it can

also drop the object when it is implied. For example, Koreans will

often say: "Saranghaeyo," which is the verb

"love". There is no subject and there is no object needed

when you are talking to the object of one's affection. It is

implied, and therefore understood by one's interlocutor. 8.

SPECIAL FONTS NOT NEEDED FOR THIS SITE I made it

possible to study Korean without needing Korean fonts. I've done

this by putting the Korean letters on gif (picture) files and uploading

them to the webpage. |

| |

| Lesson 1: Romanization of

Korean letters

Please notice that some letters are listed twice on the table

below. That's because they have more than one sound.

If you wish to learn to read Korean, your first task will be to

memorize the following information. You might want to make flash

cards and put the Korean letter on one side and the sound on the other

side.

In Lesson 4, you will learn how the letters are put together to make

words.

RE: THE "MAGIC

CHEERIO":

Korean letter: O I NEED to mention the magic "cheerio". It is a circle. It

has two usages. (1) at the end of a syllable (at the bottom), it functions as the

/ng/ sound, as in the word "sing". (2) When situated either at the left-hand side or top of a vowel (or vowel team), it has no sound.

[See table above]. The "magic

cheerio" is needed there, because vowels are not allowed to

"dangle" alone in the Korean written language. * APA =

American Phonetic Alphabet

** IPA = International Phonetic Alphabet |

| |

Lesson 2:

Numbers

Korean Has 2 (two) Numbering Systems As if

learning a foreign language wasn't hard enough, Koreans have to have TWO

numbering systems. It can get kind of confusing knowing when to

use each numbering system, but then again, it is rather simple.

The Sino-Korean numbering systems comes from China. The following

rule is not a

hard-and-fast rule, but generally whenever a number collocates with a

Sino-Korean word, the Sino-Korean number is used. And whenever a

number collocates with a pure Korean word, the pure Korean numbers are

used. As a beginner, you cannot be expected to know which words

are pure Korean and which are Sino-Korean. If you wish to find

out, simply look up the word in a bilingual dictionary. If there

are Chinese characters next to the word, it is a Sino-Korean word.

If not, it is a pure Korean word. The Korean word for its currency is Weon or Won

[pronounced: wuhn]. It comes from the same Chinese ideograph as

the Chinese word for its currency, namely Yuan, and

coincidentally, the Japanese word Yen come from the same Chinese

ideograph as well. Since the word is Chinese in origin, the

Sino-Korean numbering system is used when dealing with money. Eventually,

you will need to know both numbering systems, but at first, I recommend the Sino-Korean

numbering system, since that is the one used with money, and you will

need it to buy and negotiate prices. I will teach both here.

[Note: Koreans use Arabic numbers when writing.]

| Arabic #s |

Romanized

Pure Korean

Numbers |

Sounds like this

in North Amer.

English |

Romanized

Sino-Korean

Numbers |

Sounds like this

in North Amer.

English |

| 1 |

hana |

hahnah |

il |

ill |

| 2 |

dul |

dool |

i |

ee |

| 3 |

set |

set |

sam |

sahm |

| 4 |

net |

net |

sa |

sah |

| 5 |

daseot |

tahsuht |

o |

oh |

| 6 |

yeoseot |

yuhsuht |

yuk |

yook |

| 7 |

ilgop |

ill-gope |

chil |

chill |

| 8 |

yeodeol |

yuhduhl |

pal |

pall |

| 9 |

ahop |

ah-hope |

ku |

koo |

| 10 |

yeol |

yuhl |

shib |

ship |

| 11 |

yeol-hana |

yuhl-hahnah |

shib-il |

shibbill |

| 12 |

yeol-dul |

yuhl-dool |

shib-i |

shibbee |

| 13 |

yeol-set |

yuhl-set |

shib-sam |

ship-sahm |

| 14 |

yeol-net |

yuhl-net |

shib-sa |

ship-sah |

| 15 |

yeol-daseot |

yuhl-tahsuht |

shib-o |

shibboh |

| 16 |

yeol-yeoseot |

yuhl-yuhsuht |

shib-yuk |

shim-yook |

| 17 |

yeol-ilgop |

yuhl-ill-gope |

shib-chil |

ship-chill |

| 18 |

yeol-yeodeol |

yuhl-yuhduhl |

shib-pal |

ship-pall |

| 19 |

yeol-ahop |

yuhl-ah-hope |

shib-ku |

ship-koo |

| 20 |

seumeul |

soomool |

i-shipb |

ee-ship |

| 30 |

seoreun |

suhroon |

sam-shipb |

sahm-ship |

| 40 |

x |

x |

sa-shipb |

sah-ship |

| 50 |

x |

x |

o-shib |

oh-ship! |

| 60 |

x |

x |

yuk-shib |

yook-ship |

| 70 |

x |

x |

chil-shipb |

chill-ship |

| 80 |

x |

x |

pal-shib |

pall-ship |

| 90 |

x |

x |

gu-shib |

koo-ship |

| 100 |

x |

x |

baek |

back |

| 1000 |

x |

x |

cheon |

chun |

| 10000 |

x |

x |

man |

mahn |

See any patterns? 10,000 Won is like $10 U.S., so

you'll need to count higher than that. It's easy. 20,000 is just

2 x 10,000; say: "ee-mahn". Koreans count the same way

the Chinese do. Like this: 33,333 = 3 x 10,000 + 3 x 1,000 + 3 x

100 + 3 x 10 + 3 Say: "sahm mahn, sahm chun, sahm back,

sahm ship, sahm". __________________________________________ 100,000 = 10 x 10,000 Say: "ship

mahn". __________________________________________ 1,000,000 = 100 x 10,000 Say: "back mahn". __________________________________________ That's

really as high is you'll need to count. 1,000,000 Won is about

$1,000 U.S. |

| |

| Lesson 3: Korean Consonants

When I first endeavored to learn the Korean language, I was

introduced to many new phonemes that I had never been exposed to

previously. I was then 26 years old, way past the so-called

"critical period". I made friends with a patient native

speaker of Korea, who endeavored to teach me these new sounds.

At first, I could not produce them, because I could not hear them.

After listening over and over and given the opportunity to hear

similar sounds juxtaposed (temporally), I soon came to distinguish

(auditorily) the various sounds.

The vowels did not give me trouble except one. And I'll get to

that one later.

The consonants provided quite a challenge.

Korean has 13 consonants, but FOUR in particular, CAN BE DOUBLED

UP. Those four, plus four others provided me with quite a

challenge. The resulting twelve phonemes can be taxonimized into

four sets of three. Each set contains three consonants that are

remarkably similar to the untrained ear. In fact, they were quite

undistinguishable to me at the time I first heard them.

The sets cannot be adequately transliterated into Roman letters (the

letters you see here). But, I'll make do.

Romanized

as: |

Sounds

like: |

Romanized

as: |

Sounds

like: |

Romanized

as: |

Sounds

like: |

| g |

soft /k/ |

gg |

accentuated

/g/ |

k |

aspirated

/k/ |

| d |

soft /t/ |

dd |

accentuated

/d/ |

t |

aspirated

/t/ |

| b |

soft /p/ |

bb |

accentuated

/b/ |

p |

aspirated

/p/ |

| j |

soft /ch/ |

jj |

accentuated

/j/ |

ch |

aspirated

/ch/ |

This is what the Korean consonant-phonemes look

like, respectively:

One can plainly see that not only do the consonants (from left to

right) share a phonetic nearness, but they also share a symbolic

nearness.

As soon as I could distinguish the sounds auditorily (from left to

right), I could produce them linguistically (i.e., with my vocal

apparatuses).

The vowel sound that I had trouble with took a couple years before it

could be heard and produced (by me), but I eventually got it. And

it should be noted that it only took years, because I did not devote as

much time and energy into learning it as I did the consonants.

The reason I did not dedicate so much time to the one renegade vowel,

was because I was generally understood by my interlocutors, despite the

error. I was using the English schwa sound, which is phonetically

close, but is more like the backwards "c" (in IPA).

|

| |

| Lesson 4: How to read Korean

Please refer to the above chart on How to read Korean for

this lesson

Vowels can be attached to the right side of a consonant

(as in 1), or below the consonant (as in 2), but it must be noted that

only CERTAIN vowels can go to the right and CERTAIN others can go below.

If you look at lesson one: vowels. The top eight

vowels can go to the right, while the next five go below, and the last one

goes to the right.

Number 1 is Romanized as "ga", but since it is a

beginning sound, the "g" is pronounced like a soft

"k". It means "go" (but it is the most familiar

and least honorific, i.e., not honorific at all). [See lesson five

about Korean honorifics].

Number 2 is Romanized as "go", but since it is a

beginning sound, the "g" is pronounced like a soft

"k". It is a family name in Korea. It also means

"high".

Number 3 is "ga" + "go". Since

the "ga" is first, it sounds more like a soft

"ka". Since "go" is second, it is pronounced as

it is written. The word "kago" could mean: "a

fresh start", or present participle of 'to go', or "go,

and...".

Number 4 is Romanized as "jab", but the

"j" (at the beginning) sounds more like a soft "ch",

and the "b" is NOT pronounced (i.e., voiceless). It sounds

more like "chap". It means: miscellaneous, or root of the

verb 'to grab'/'to take'.

Any consonant at the bottom of a syllable is NOT

pronounced (I mean it is voiceless), except "n", "m",

"l".

Number 5 is Romanized "a". The "magic

cheerio" is not pronounced. It is just there to groom the vowel

"a". If one were to ad 5 to 4, one would get "chaba".

By adding a vowel, the previous consonant becomes "activated"

and voiced. "Chaba" (with a very SOFT "ch"

sound) means grab (in the familiar or least honorific sense).

Number 6 is Romanized "eung". It would be

like this (in IPA) :

| / |

|

|

/ |

It means "uh,

huh" or "yep".

[You can see the magic cheerio at the top (no sound), and

at the bottom, (sounding like "ng"].

Number 7 show some Korean dipthongs: "oa"

and "oi".

"oa" is pronounced like

IPA /wa/, and "oi" is pronounced like IPA /we/.

"oa" means 'and'.

"oe" means 'outside' / 'extra~'

Number 8 show some more Korean dipthongs: "oae"

and "ui".

"oae" is pronounced

like IPA /we/, "ui" is pronounced like IPA /wi/.

"oae" means

"why" (but more familiar and least honorific). "ui-e"

means 'up' (adv.) / and "ui-jang" means 'stomach' (as in the

organ).

|

| |

| Lesson 5: Korean

Honorifics

Let's go with some of the examples used above for reinforcement and

extrapolation.

We've learned that ga (pronounced "ka") is the

familiar and least honorific form of "go".

Korean Honorifics is a bit complex, but in time, you'll get it.

Many books will tell you that there are three levels. This is

false. There are actually FOUR levels,

and usage is of paramount importance.

Here are the levels, using "ga":

| infinitive |

low |

middle |

high |

highest |

| gada |

ga |

gayo |

gamnida |

gashimnida |

Usage:

ga is used to someone who is familiar AND of equal or inferior

status.

gayo is used to someone who is not familiar, but appears to be

of equal or inferior status.

gamnida is used to someone who is clearly of superior status,

and only when talking about one's self or others of equal or inferior

status.

gashimnida is used to someone who is clearly of superior

status, and only when talking about one who is of superior status.

Further extrapolation:

There are other forms as well, with other usages. It gets

extremely complex, and you may not care to know any more at this point,

but if you do, here you are:

gashyeo is used to a familiar person of equal or inferior

status when talking about someone of superior status.

gashyeoyo is used to someone less familiar of equal or

inferior status when talking about someone of superior status.

Then, you can add tenses and moods and imperatives and it gets

REALLY complex.

Are you freaked out yet?

I was oblivious to all the forms when I first started learning Korean

and ignorance is bliss, I guess. Later, when I started learning

all the forms, I started freaking, but only a little. I actually

thought it was cool, because Korean has many forms that don't exist in

English, but are lovely and useful.

Many ideas, moods, feelings, illocution in English are expressed by

suprasegmental features of the SPOKEN language and cannot be written

down (well not with type writers or word processors). But, in

Korean, many such ideas, moods, feelings and such can be expressed both

in spoken AND written form. This is an advantage of Korean over

the English language.

This is also why Koreans have never won a prize for literature, ...

because it is impossible to translate the Korean forms into English and

maintain the same nuance.

Korean is a very, very beautiful language, and I hope it never gets

lost from this earth or this universe.

Another example: Above, I wrote that "oa"

(pronounced /wa/) means "and", and that is correct, but it

also means "come" in the lowest form. It is an irregular

verb and the conjugation is a bit strange. See table below:

| Infinitive |

low |

middle |

high |

highest |

| oda |

oa |

oayo |

omnida |

oshimnida |

|

| |

| Lesson 6: The

Korean Imperative

It is imperative that you know how to use the Korean imperative

correctly. Otherwise you could get into trouble.

There are, of course different levels of "honorifics"

involved in using the imperative. Let's look at the verb ga

which means "go".

You can say, "Ga," which means:

"Go." But it conveys the same usage as in English, i.e.,

a command to someone of equal or inferior status and to someone who is

familiar. You could also say, "Gara," which

carries heavy weight if the speaker has definite authority over the

audience. It also implies that there is no option, for to disobey

means serious consequences. There is no equivalent in the English

language, but perhaps a very good translation would be: "Thou

shalt go." Finally, you can add the suffix "seyo"

(middle form) or "shipshio" (highest form) to the verb stem ga

as honorific commands.

Korean also has what I call 'compound verbs' (i.e., two verbs

attached). If one were to add the verb juda (give)

to another verb (used in the imperative mood), then it becomes more

polite. It is a lot like adding "please" in English,

which originally was used as a verb thusly: "...if you

please", but has been shortened to "please" in modern

times.

So, this is what it all looks like:

| No. |

Form |

Word-for-word

translation |

Literal

translation |

Free

translation |

| 1 |

ga |

go |

go |

go |

| 2 |

ga-ra |

go shalt |

[thou] shalt go |

thou shalt go |

| 3 |

ga-seyo |

go

[+ mid honorific suffix] |

go

[cannot translate honorifics] |

go, if you

please |

| 4 |

ga-shipshio |

go

[+ highest honorific suffix] |

go

[cannot translate honorifics] |

go, if you wouldn't mind,

please |

| 5 |

ga-jueo |

go give

[+ low honorific, i.e, no suffix]

[familiar form] |

give [to

me your] going

|

I think it means:

"Give me the pleasure of your going." But,

loosely translated, it means:Please go |

| 6 |

ga-juseyo |

go give

[+ mid honor] |

give [me your] going

[cannot translate honorifics] |

Pretty

Please, go |

| 7 |

ga-jushipshio |

go give

[+ highest honor] |

give [me your] going

[cannot translate honorifics] |

Pretty Please

With Sugar and Honey on top, Go |

Notice that there are three kinds of translation:

1. word-for-word, where the words are translated exactly

in the order that they appear in the first language and no other words

are added.

2. literal translation, where the words are rearranged

to match the syntax of the second (target) language, and necessary words

(or suffixes) are added to give the appropriate meaning.

3. free translation, where words, suffixes and syntax

are disregarded and only meaning is translated (and I should

add... "as best as possible").

[Note: I hope many Koreans read this

page, because it is generally assumed by Koreans that English does not

have levels of politeness in its imperatives. Of course, they

should know "please", but often fail to use it, thinking

erroneously that it is not needed. If you are an English teacher,

please do what you can to eradicate these myths about English that exist

in the collective Korean mentality.]

Now for usage. Refer to the table above and the numbers of the

forms...

1. usage mentioned above

2. usage mentioned above

3. usage is to someone less familiar of equal or inferior

status

4. usage is to someone more familiar of superior status

5. usage is to someone very familiar of equal status (to be

polite)

6. usage is to someone not familiar at all of equal status, or

to someone familiar of superior status

Like, you would use this form to a taxi

driver, stating the destination first.

7. usage is to someone clearly of superior status (to show

ultimate respect)

Determining STATUS in Korean

society.

One might ask (if she/he is a foreigner/expatriate): "How

do I determine social status of my interlocutor?"

This is not so simply answered. In fact, it can get quite

complex at times.

There are several factors involved in determining status:

Color code: red = more

honor; blue = less honor

1. Age (older vs. younger)

2. Marital status (has married

vs. has not)

3. Relationship (ex.: teacher : student;

employer : employee;

customer : host)

4. Perhaps ages ago: gender, but not now.

5. Occupation (professional vs. laborer)

Simple? WRONG!

Here are some "what-ifs" to consider:

1. What if your the teacher in an academy and one of your adult

students is older than you?

2. What if your spouse is the youngest child in his/her family

and his/her ELDER sibling is younger than you?

3. What if you are the customer (customer is king in Korea),

but your host is older than you?

4. What if your colleague is older than you, but you are

married and she isn't?

5. What if you are a single professor, and your

acquaintance of equal age is a married laborer?

In the past (according the Confucian values), I'm sure there were

"rules" for all such hypothetical (and real) scenarios, such

as the ones above. However, Koreans are not being formally

educated about the Confucian values and they are sometimes confused

themselves (as I have asked them).

But, this was the general consensus from my students:

Scenario 1: Teacher is one of the highest positions in

the Confucian system. In fact, there is a saying: King,

Scholar, Father: one in the same. (and a teacher is considered a

scholar). The teacher, therefore, deserves the utmost

respect. HOWEVER, (and this is a big however), in Korean society,

an academy teacher is considered of lower status than a public school

teacher, who is of lower status than a professor. FURTHERMORE, the

student in an academy is also a customer and customer is king. In

short, my students said that both should be offered equal respect in the

highest honorifics.

Scenario 2: This was a true scenario. My wife was

the youngest. Her elder brother was younger than I. Upon

asking, I was told that my status in the family was equal to my wife's

status, therefore, I was lower than her brother. However, (they

added), that is in the past, and we should offer equal respect in the

middle form to each other.

Scenario 3: In this case, you are higher, but I've found

that the more respect you give to your host, the better the service you

get.

Scenario 4: This is a toughie, because in Korean and

China a woman is not considered a "woman" until she gets

married; BUT, Age is a line that rarely crossed when dealing with

honorifics. It could go either way. A second factor would

have to come into play (and usually does). For example, if you

have children, you would definitely be higher. If she had

seniority in the company, she would definitely be higher (based upon the

relationship). (Seniority is determined by how long one has worked

for the company).

Scenario 5: This one is a toughie! One would have to be

an expert in the Confucian value system in order the answer this

definitely. It all depends on which is valued more, education or

marriage. If I had to guess, knowing that the whole Confucian

value system is base upon education, I would guess that the professor

would be higher and would command more respect, but would be constantly

chided by others about his single status.

In Korean society (and this may have NOTHING to do with Confucius) a

man is not a "man" until he gets married. So, this case

is really a toughie. Thus, when in doubt, always use the highest

form.

I'll tell you a story. (It's

true).

One day, in Korea, I met a elderly blind woman. We started

talking (in Korean, of course). She couldn't see how old I was (I

was 26, and academy instructor, and unmarried at the time).

She asked, "How old are you?"

(always the first

question Koreans ask, and she used the ultra high/polite form of the

Korean honorific system).

I answered, "I'm twenty six."

{in the high form

(which is the highest form for talking about one's self)}

Then she asked, "What work do you do?"

(dropping down

one level in honorifics).

I answered, "I'm a teacher."

(staying with the same form as I previously used).

Then she asked, "Where do you work? A public school or an

academy?" (same form as before).

I answered, "In an academy."

She, then asked, "Have you gotten married?"

(dropping

down a notch in honorifics).

I answered, "No."

She, then, said, "Oh, you are a boy!"

(in the lowest

form possible).

|

| |

| Lesson 7: The

Korean Interrogative

Using ga (the verb "go")...

"Where do you go?" can have four different forms,

depending upon one's interlocutor. See table below:

| low |

mid |

high |

highest |

| eodi ga? |

eodi gayo? |

eodi gamnigga? |

eodi gashimnigga? |

What I wrote about usage of the honorifics in lesson five, applies

here.

Special Grammar Note: there are only two words in the Korean

sentence, and four in the English sentence. This is because

grammar is different.

Korean is what is called a "pro-drop" language. That

means the subject can be dropped. English (and possibly other

Germanic languages) is/are the only language(s) that use "do"

in the interrogative, so you can forget about that.

So, the Korean sentence is: "Where go?"

It is very comfortable AND convenient to leave off the subject when

the subject is known. It didn't take me long to get used to it,

because Spanish is another pro-drop language and I was already used to

that.

|

| |

| Lesson 8:

Requesting in Korean

Requesting is a very useful function of language. Like, I

didn't like using the Korean imperative (as polite as it may be).

I was more comfortable with the request.

Let's use the Korean word hada (which means:

"do").

By dropping the infinitive ending "da" & adding a

suffix (lae, laeyo, shilaeyo), without tone, you can say, ((sb))

"Want to do" ((sth)).

By using a rising tone at the end (just like English), you can say,

((sb)) "Want to do?" ((sth)).

Interjection: I mentioned in the previous lesson that Korean is

a subject-pro-drop language. It is also an object-pro-drop

language, which means the object of the sentence can be dropped, when

previously mentioned, and therefore is known.

This form "Want to do" can function as an question OR a

request. See table below

| Description |

Korean |

English |

| infinitive |

hada |

to do |

| low |

halae |

want to do |

| mid |

halaeyo |

want to do |

| high/highest |

halaeyo |

want to do |

| |

|

|

compound

low |

haejulae |

would do |

compound

mid |

haejulaeyo |

would do |

compound

high/highest |

haejushilaeyo |

would do |

Some examples:

1. to one's wife: "Bap halae?"

word-for-word

translation: "Rice do-want?"

literal

translation: "Do you want to do rice?"

free

translation: "Do you want to make rice?"

illocution:

"Will you make rice?" (request)

nuance:

a little rude, if you ask me, but many Korean men use this form, or the

even ruder form "bap jueo" (Give rice!); However, to be

fair, they do say it sweetly, and softly.

2. to one's wife: "Bap haejulae?"

word-for-word

translation: "Rice do-give-want?"

literal

translation: "Do you want to give [for me] the doing of

rice?"

free

translation: "Would you make rice for me?"

nuance:

a lot more polite; it's the form I would use.

applied

linguistic note: SOME (not all) older Koreans insist upon using middle form to

one's spouse, by adding the "yo" on the end. But, the

X-generation of Koreans do not insist upon it. There appears to be

a variation in usage based upon social status, and region.

3. to waitress: "Bap julaeyo?"

word-for-word

translation: "Rice give-want?"

literal

translation: "Do you want to give rice?"

free

translation: "Would you give rice?"

nuance:

This form is very polite to a waitress, but not polite to one's

mother-in-law. Most Koreans say, "Bad juseyo." (Please

give rice.), but I find that using the request rather than the

imperative makes the waitress very happy, and she happily serves you the

rice. And isn't that what we all should be doing... is spreading a

little cheer here and there? Then again, if everyone used the

request instead of the imperative, it wouldn't make the waitress any

happier than normal, would it? In my case, I prefer to have my

food served without bugs, hair, and/or saliva in it. Plus I like

good service. That's why I use the more polite forms to

waiters/waitresses.

To one's mother-in-law or boss's wife, if (and only if) one is

offered rice, AND if one eats all and wants more, one can say, "Bap

jeom deo jushilaeyo?"

word-for-word

translation: "Rice a little more give want?"

literal

translation: "Do you want to give me a little more

rice?"

free

translation: "Would you give me just a little more rice,

please?"

|

| |

| Lesson 9: Korean

Honorific Word Changes

Sometimes, one must use a completely different word in order to be

"honorific" in one's speech.

For instance, see the table below:

| English |

Regular Korean word

(infinitive) |

If you have

Korean

Fonts: |

Honorific Korean word

(infinitive) |

If you have

Korean

Fonts: |

| eat |

meokda |

먹다 |

japsushida* |

잡수시다 |

| be (exist) |

itda |

있다 |

gyeshida* |

계시다 |

| drink |

mashida |

마시다 |

deushida* |

드시다 |

| sleep |

jada |

자다 |

jumushida* |

주무시다 |

| house/home |

jip |

집 |

daek |

댁 |

*NOTE: These are the infinitive forms of the verbs. So,

they must be conjugated with honorific suffixes! See lesson five

to learn how to do so. |

| |

Lesson 10: Korean

Culture and Language:

Especially regarding: Titles and Pronouns

VERY

IMPORTANT!

VERY

IMPORTANT!

You cannot separate language and culture. Culture is imbedded

in the language. In no other language that I know, except perhaps

Japanese, is that more true, than in the Korean language.

Of course, the Confucian value system has influenced the honorifics

(or perhaps the Koreans had a similar value system long before Confucius

came along). I don't know, and I don't know anyone who does.

But, the point is, the values of the Korean people have influenced their

language.

Furthermore, the usage of titles and pronouns is very, VERY important

(to Koreans). Knowing when to use which titles and which pronouns

(if at all) is very helpful when speaking Korean.

For instance, in English, we throw around the second person pronoun

"you" with no though about honorifics or about possibly

offending somebody with its use. [Of course it is the honorific

form, and the more familiar "thou" has become completely

obsolete]. Korean has four forms of the pronoun

"you". Terms (metalanguage) for the four forms does NOT

exist in English, so I'll have be creative...

| Korean |

Romanization |

lay-man's APA |

IPA |

Meaning

and Usage |

| 너 |

neo |

nuh |

n |

Second person singular, low form

(i.e.,

not honorific) |

| 너희들 |

neo-heui-deul |

nuh-hee-dl |

n -hi:-dl -hi:-dl |

Second person plural, low form |

| 당신 |

dang-shin |

dahng-sheen |

dang-shi:n |

Second person singular, high form (honorific,

but used today with spouse only)

To others, titles are used (rather than "you") See

more info below

about titles. |

| 당신들 |

dang-shin-deul |

dahng-sheen-dl |

dang-shi:n-dl |

Second person plural, high form

(I've never heard this used, as nobody has more

than one spouse). |

After learning these, I was under the natural assumption that the

honorific form could be used toward strangers, much like the "usted"

form in Spanish. Oh, how wrong I was!

One day, I went into a bakery with a Korean friend to buy some

bread. I saw a picture of a little girl, and I asked the shop

owner, "Dangshin-eui ddal imnigga?" [Is that your daughter?] I used the honorific

form of the verb, even. My Korean friend said that I was so

rude. I said, "What are you talking about? I used the

honorific form! Why am I rude?"

My Korean friend explained that in Korean, one only addresses one's

betrothed or spouse with the "dangshin" title. I said,

"How was I supposed to know that? Nobody taught me

that!" Not even the book that I was using to learn Korean

mentioned anything about that. In fact, I think you won't find any

book on the market that teaches Korean that will tell you that.

So, I asked my friend, "What am I supposed to say, then?

How do I address people?" He replied, "With the titles ajeoshi

and ajuma."

Now, the bilingual dictionaries all translate ajeoshi as

uncle and ajuma as aunt. This is SOOOOOOOO

wrong. [See my Bilingual Dictionary

Errors Page for more egregious errors.]

NO KOREAN would EVER call their blood uncle or aunt by either of

those titles. In fact, to do so would be so extremely rude that

they would get a beating for doing so. So, we cannot trust

the bilingual dictionaries.

Ajuma is a title for a woman, who is married (or

has been), AND has a child approximately your same age (give or take 10

years). [From my research, the word is composed of 2 morphemes: aju

(just like) + ma (mother). So, it refers to a woman who is

just like one's mother].

Ajeoshi is a title for a man, who is older than

one's self AND married AND has a child approximately your same age (give

or take 10 years). [The word is obviously composed of 2 morphemes:

ajeo (?) + shi (kin). If I had to guess, I'd guess that ajeo

is a variation of aju. So, my best guess is it literally

means: just like kin.]

Those explanations of ajuma & ajeoshi are quite apropos,

because in Korean culture, all women and men who are near the same age

as one's parents are considered like kin.

OTHER TITLES:

Samchon: /sahm-chone/ [literally means

one's father's brother] can be used for a man who is not a blood

relative, but is a close friend of one's father.

Imo: /ee-moh/ [literally means one's

mother's sister] can be used for a woman who is not a blood relative,

but who is a close friend of one's mother or simply a female mentor.

Hyeongnim: /hyung-neem/ [literally means

elder brother of a male + respectful suffix "nim"] can

be used only by males to an older male, who

is not old enough to be an ajeoshi. NOTE:

because of the suffix, it is considered very formal. To be

informal, just drop the suffix. Generally, from my observations,

children do not use the suffix to older children. But, men use it

to older men.

Obba: /oh-BBah/ [literally means elder

brother of a female] can be used by females to an older male, who is not

old enough to be an ajeoshi. NOTE:

considered informal. If females wish to be formal, I think they

use the title seon-seng-nim /sun-seng-neem/

[literally means: firstborn].

Jamaenim: /jahmay-neem/ [literally means

elder sister + respectful suffix "nim"] can be used to a

woman who is older but not old enough to be an ajuma. NOTE:

it is considered very formal. It appears to be used by both men

and women.

Nuna: /noo-nah/ [literally means elder

sister of a male] can be used by any male to any older female, who

is not old enough to be an ajuma. NOTE:

considered informal.

Eoni: /uh-nee/ [literally means elder

sister of a female] can be used by any female to any older female, who

is not old enough to be an ajuma. NOTE:

considered informal.

You will notice that all of the titles mentioned above are for

persons older than oneself. If one is addressing a person younger,

one may use the person's name.

However, if one does not know the name of his/her younger

interlocutor, there are some titles that can be used:

Agashi: /ah-gah-shi/ [composed of 2

morphemes: aga (baby) + shi (kin)] can be used

by any adult male to any younger adult female. NOTE:

I've never heard a female Korean use the word, so I guess it is

forbidden. It is generally used by older men to younger women.

Aideul: Sounds like "Idle"

[literally means children] can be used to a group of children

(obviously younger than oneself).

Ai: Sounds like "I"

[singular of above] can be used when talking about a child

Aga: /ah-gah/ [literally means baby]

can be used to babies and toddlers (obviously younger than oneself.

Aegi: /ay-gee/ [variation of aga]

A VERY IMPORTANT TITLE TO LEARN:

Seon Seng Nim.

Seon means first (from

Chinese); Seng means born

(from Chinese); Nim is a suffix of respect, much like Sir or

Ma'am (It is pure Korean).

It has two usages:

1. To any person who is older and respected as a kind of

mentor.

2. To any teacher (regardless of age).

Incidentally, in China, it (xian sheng) is used only in the first sense.

|

| Lesson 11: Restroom

Talk

Probably the most important thing you will ever

learn in any foreign language is: "Where is the

restroom/toilet?"

Koreans have only one way to say it, but that

"way" can be different depending upon the level of

"honorifics" chosen by the speaker. If you really want

to learn all about Korean honorifics, see lesson 5.

| Honorific level |

For those with Korean fonts |

For those without |

| high form |

"화장실(이) 어디

입니까?" |

"Hoa-jang-shil (i)

oe-di ibniGGA?" |

| middle form |

"화장실(이) 어디

이예요?" |

"Hoa-jang-shil (i)

oe-di i-ye-yo?" |

| low form |

"화장실(이) 어디 야?" |

"Hoa-jang-shil (i)

oe-di-ya?" |

NOTE: Using the "low form"

is rude, unless you know how and when and who to use it with. See

lesson 5 about honorifics.

Linguistic Notes:

The "i" or "ee" in parentheses is

optional. It is the subject marker, indicating that the noun is

being used as the subject of the sentence. It may seem strange to

have subject and object markers, as Korean does; but, actually, it makes

for a convenience sometimes, because the subject can be dropped and only

an object used. See lesson 12 for more information on this.

The "GGA" is capitalized, because it should

be stressed. As mentioned above, All syllables containing double

consonants must be stressed. In English, we don't usually stress

the last syllable of a sentence, unless we are angry. So, Koreans

often sound as if they are angry to us foreigners. It takes a long

time to get used to it.

Not that you would want to, but...

Here's How

to talk about excrement in Korean:

똥/응가/대변 (ddong, eung-a, dae-byeon)

1. excrement = 배설물 /bae-seol-mul/

2. dung = animal solid excrement

3. poo / poo poo / poop = young child's word = 응가 /eung-ga/

or /eung-a/ (origin: sound of squeezing "eung" + sound of relief "ahhh")

4. doo / doo doo/ doodie = (see #3) (also see: http://www.doodie.com)

5. crap = [from French] general word for waste (but often: human waste)

6. shit = abusive word (Ex. You are a little shit!)

7. manure = [from French "hand"] farmers' word, because the farmer shovels the animals' manure by hand and uses it to fertilize the

crops = 두엄 /du-eom/, 퇴비 /twe-bi/

8. feces = scientists' word = 대변 /dae-byeon/

9. stool = doctors' word = 대변 /dae-byeon/

verbs:

1. go poo poo = 응가를 하다 /eung-ga-reul ha-da/

2. take a crap/shit = idiom (not nice) = 똥을 쌓다 /ddong-eul

ssah-da/

3. go #2 = idiom (nice) = 대변을 쌓다 /dae-byeon-eul ssahda/

*********************************************************************

And: Liquid

Excrement

RE: 오줌/쉬/소변 (o-jum, shee, so-byeon)

1. pee /pee pee = young child's word = 쉬 /shee/

2. urine = scientist and doctors' word = 소변 /so-byeon/

3. piss = slang word (not nice)

verbs:

1. go pee = 쉬를 마리다 /shee-reul ma-ri-da/

2. urinate = 소변을 쌓다 /so-byeon-eul ssah-da/

3. piss = (not nice) 오줌을 쌓다 /o-jum-eul ssah-da/

4. go #1 = (nice)

*********************************************************************

RE: Korean Restroom Idioms

1. I have to answer a "nature" call. = 볼일 보고 오께요. /bo-ril

bo-go o-gge-yo/

[literally means: I'll see about something and come back.]

2. Did everything come out all right? = 시원하세요? /shi-weon ha-se-yo?/

[literally means: Are you cooled-off now? (because you

know... you get a breeze when you pull your pants down. But, that

word has another slang meaning, which is: do you feel better

now? So, because of the double meaning, it's a kind of Korean double

entendra.... pretty funny when you think about it.]

|

| |

| Lesson 12:

Restaurant Talk

If you want to eat: I suggest you start learning the vocabulary

on my KOREAN

FOOD page.

Here's some other useful words/phrases in Korean language when

eating out in Korea.

Korean

Word

(Romanized) |

Translation

(Word-for-word)

Note: Korean syntax used here!

See lesson 13 for more details. |

Mnemonic

Device |

| menyu |

menu (abstract meaning) |

X |

| menyu pan |

menu board |

pan is pronounced like 'pawn' in

North American English.

So, think that the menu is like a pawn in the whole process

of getting you what you want: namely FOOD! |

| Menyu pan jeom juseyo. |

Menu-card (?) give please.

(Honorific version) |

Menu-Pawn, jump! Joo say,

"Oh!" |

| An-mepge hae-juseyo. |

Not-spicily make please.

(Honorific version) |

On map Gaigh; Hey! Joo say,

"Oh!" |

| Mepge hae-jusheyo. |

Spicily make please. |

Map Gaigh; Hey! Joo say,

"Oh!" |

| Mash(i) isseoyo. |

Taste (flavor) exists.

(meaning: it's delicious). |

Marsh [salt] is so [?] Yo! |

| Mash(i) eopseumnida. |

Taste (flavor) doesn't exist.

(meaning: it's not delicious). |

Marsh [salt] up! some need, Ah!. |

| "Service" jo-a-yo. |

[The] service is good. |

Service: Joe-Ahhhhhhhh--Yo! |

| "Service" an-jo-a-yo. |

[The] service is not good. |

X |

| "Service" juseyo. |

Service, please. |

Service: Joo say, "Yo!" |

| Mul |

Water |

[Makes

me cool] = Mool |

| Mul juseyo. |

Water, please. |

Mool,

Joo say, "Yo!" |

| Maek-ju |

Beer |

Make you [drunk]. |

| Maek-ju deo juseyo. |

Beer, more please. |

X |

| Bap |

[Cooked] Rice |

"Bop!" [is the sound that the

rice-cooker makes when the rice is done]. |

| for more food items... |

see my KOREAN

FOOD page |

X |

|

| |

| Lesson 13: Korean

Grammar: Syntax

OOOOO! Thirteen! Scary! Right? Well, it is

true that the number 13 does signify "death" in numerology,

but it is more a figurative death, rather than a literal one.

Think of this lesson as the "death" of your fear of Korean

grammar. He, he.

Please do not be frightened of Korean Grammar. While it is

different from English grammar, it is learnable. Sometimes

translation may be difficult, and metalanguage (for describing Korean

grammar) may be somewhat lacking, but I am confident that we can

"make do". So, for those of you who are getting really

serious about learning Korean, I give you:

My Explanation of the Korean Grammar (with help from the late, great

Dr. Ramstedt of Finland).

I think that the best place to start is I give you a sentence with

every part of speech in it. So, that's what I shall do. I

will translate the following English sentence into Korean for you, so

that you might learn Korean syntax.

| I |

truly |

like |

the |

lovely |

Korean |

language. |

| subject

noun |

adverb |

verb |

article/

determiner |

adjective |

adjective |

object

noun |

| subject |

adverb |

verb |

object of

sentence |

| Now,

have a look at the grammar of the Korean Language, if you would.

(below) |

| 내가 |

- |

아름다운 |

한국 |

어를 |

진심으로 |

좋아함니다 |

| Naega |

- |

areumdaun |

hangug |

eoreul |

jinshimeuro |

joh-a-hamnida. |

| I |

- |

lovely |

Korean |

language |

true-heartedly |

like |

| noun

+ sub. particle |

no articles

in Korean |

adjective |

nominative

adjective |

noun

+ obj. particle |

adverb |

verb |

| subject |

- |

object of

sentence |

adverb |

verb |

| While

the sentence above is grammatically correct in the Korean

language, you probably will never hear a Korean speak that

way. They prefer to use passive voice, rather than active

voice. So, here is how a native Korean would say it... |

| Naneun |

jinshimeuro |

hangugeo

(ga) |

johayo. |

- |

| In my case |

true-heartedly |

Korean

language |

is liked. |

- |

| - |

adverb |

subject |

passive

verb |

- |

Need I say more? Well, yes, I do. You need to get used to

talking in the passive voice whenever possible. Sometimes it is

not possible.

Furthermore, I forgot to mention prepositions, which are actually postpositions

in Korean.

Let's analyze what we've learned, before I teach postpositions.

Korean is a S-O-V language. That means Subject-Object-Verb.

One thing is constant in the Korean language: the verb is ALWAYS

last.

The subject can be dropped, but if it isn't dropped it is usually

first.

The object comes in the middle.

Adjectives come before the nouns.

Adverbs come before the verb.

Okay, now... About postpositions in Korean.

| Elvis |

is |

in |

the |

house. |

noun

subject |

verb

(existential) |

preposition |

article

(determiner) |

noun

(object of preposition) |

| |

| 엘비스 |

이 |

집 |

안에 |

있습니다. |

| Elvis |

i |

jib |

an-e |

isseumnida. |

noun

subject |

determiner

(this) |

noun

(object of postposition) |

postposition

(in) |

verb

(existential) |

As you can see the postpositions come after the noun.

Adjectives and Adverbs (AKA: Modifiers) come before the word they

modify.

So, now you know Korean syntax. It's as simple as that.

So, start making your own sentences!

Of course there is a lot more to grammar than just syntax... maybe

I'll teach more later.

|

Learn

ALL about Korean food on Leon's Planet!!!

This will help you learn the Korean language!

P.S.

This will help you to learn the Korean language as well;

My Konglish Page!

Recommended books to learn Korean

Recommended Links related to Korea

| |

English |

|

Spanish

|

Korean |

Mongolian |

Chinese |

|

Parents of

Homeschool

|

|

Halloween

|

|

Thanksgiving

|

|

Winter Solstice

|

|

Christmas

|

|

New Years

|

|

Chinese Lunar

New Year

|

|

Valentine's

|

|

|

|

Easter

|

|

All About

Dr. Seuss

|

|

Roald Dahl

|

|

Prepper's

Pen |

|

Ways to

Help

Leon's Planet

|

|